The Latest News From MVIHES

Whether we're tracking Cutthroat Trout with scanners and antenna arrays in Shelly Creek, pruning a man-eating Raingarden at the Fire Hall, or observing Coho Salmon spawing on our latest fish habitat restoration project, there's never a dull moment with MVIHES.

Parksville Fire Hall Raingarden

On November 9, fourteen volunteers pruned, clipped, and chopped three truck and trailer loads (725 kg) of unruly vegetation from the Raingarden in front of the Fire Hall. This is in addition to the four loads we removed in March.

The Raingarden was built by MVIHES and the City of Parksville in 2012 and was planted with native vegetation. Over the following eight years it grew into an unsightly, impenetrable jungle and was unrecognizable as a Raingarden. Even the sign was swallowed up by vegetation. We've since learned that the Raingarden needs to be treated like a regular garden despite having natural vegetation.

Now you can see individual plants. One more day of manicuring and the Raingarden should be transformed into something we can take pride in again. Some light pruning every year should keep it looking attractive. To read more about the Raingarden and its purpose, check out our last article on the Raingarden .

Shelly Creek Cutthroat Trout PIT Tagging Study

There are now 52 Cutthroat Trout with PIT Tags containing transponders for tracking the trout and determining their home range in Shelly Creek.The study has been ongoing since June and is lead by Ally Badger, a fourth year Biology student from Vancouver Island University. Ally has been using a scanner that looks like a metal detector to track the movements of the tagged fish, as seen in the left-hand photo.

Since our last article on the Shelly Creek PIT Tagging Study, two antenna arrays have been installed in the creek that can pick up movements of the fish on a continual basis for several years. When a tagged fish swims over an array, the code in the PIT Tag is picked up and stored in a data collector along with the time and date of the event. This is an extension of Ally's study. One of two antenna arrays for tracking tagged trout.

The antenna arrays and data collectors are powered by four car batteries that are changed out by volunteers with a second set of charged batteries every two weeks. Due to the value of the equipment and its importance to the study, it's being guarded by a gang of Hobbits in a secure location in the Shire, so those thieving Goblins can just forget about searching for it.

Each array is connected to its own data collector Four car batteries power the arrays and data collectors

Ally will complete her field work in February 2022 and write up the findings in her fourth year thesis which she will present at a fisheries conference in Vancouver next June.

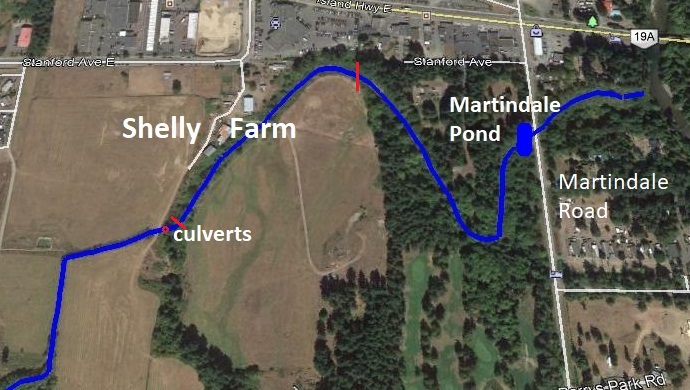

Shelly Creek Habitat Restoration - Phase II

Great news about the 400 m of creek that was restored this summer on the Shelly Farm! About 25 Coho Salmon were observed spawning there on November 4, by our favourite Biologist, Dave Clough. Woohoo!

Below are photos taken in early September immediately after the completion of the restoration work compared with photos taken at the beginning of the rainy season. Notice how the grasses we seeded for erosion control have come up like "gang busters". For details on the restoration work, check out our last article.

Restored creek bed in September Restored creek bed in November

Pond (created for refuge from summer drought) in September Pond in November

That's all folks......for now.