Ballenas ROAMS Students and Teacher Invade the Wetlands!

On October 18, twenty three ROAMS students from Ballenas high school and their teacher, Heather Quinn, helped the City of Parksville Parks Department plan 500 trees, shrubs and sedges in the Parksville Wetlands.

ROAMS stands for Rivers, Oceans, and Mountains School and is an outdoor leadership program which focuses on career preparation, work experience, adventure education and community leadership in School District 69. Joining Parks staff in planting the seedlings was made possible through an Action Plan developed by student Emily C as part of her course curriculum. You can see the students in action below.

So how do the Parksville Wetlands help salmon?

About 70% of the water supplied to Parksville comes from the Englishman River. We know that flow in the river gets very low in summer and early fall which can negatively impact juvenile and spawning salmon. Watering restrictions come into effect during this time to keep more water in the river.

The other 30% of the water supply comes from wells that are fed by an aquifer lying beneath the Parkville Wetlands. Without the water from these wells, all of Parksville's water would come from the Englishman River in the summer. You can imagine the impact that would have on salmon.

The vegetation and soil in the Wetlands collect and store rainwater and allow it to percolate into the ground which helps feed the aquifer. Keeping the Wetlands healthy through planting native vegetation in areas degraded by human activity will benefit the wells and take some of the pressure off the Englishman River.

You may remember that this time last year, 40 volunteers came out to plant in the Wetlands. Those plants are looking pretty good as seen by the Douglas fir and rose in the photos above.

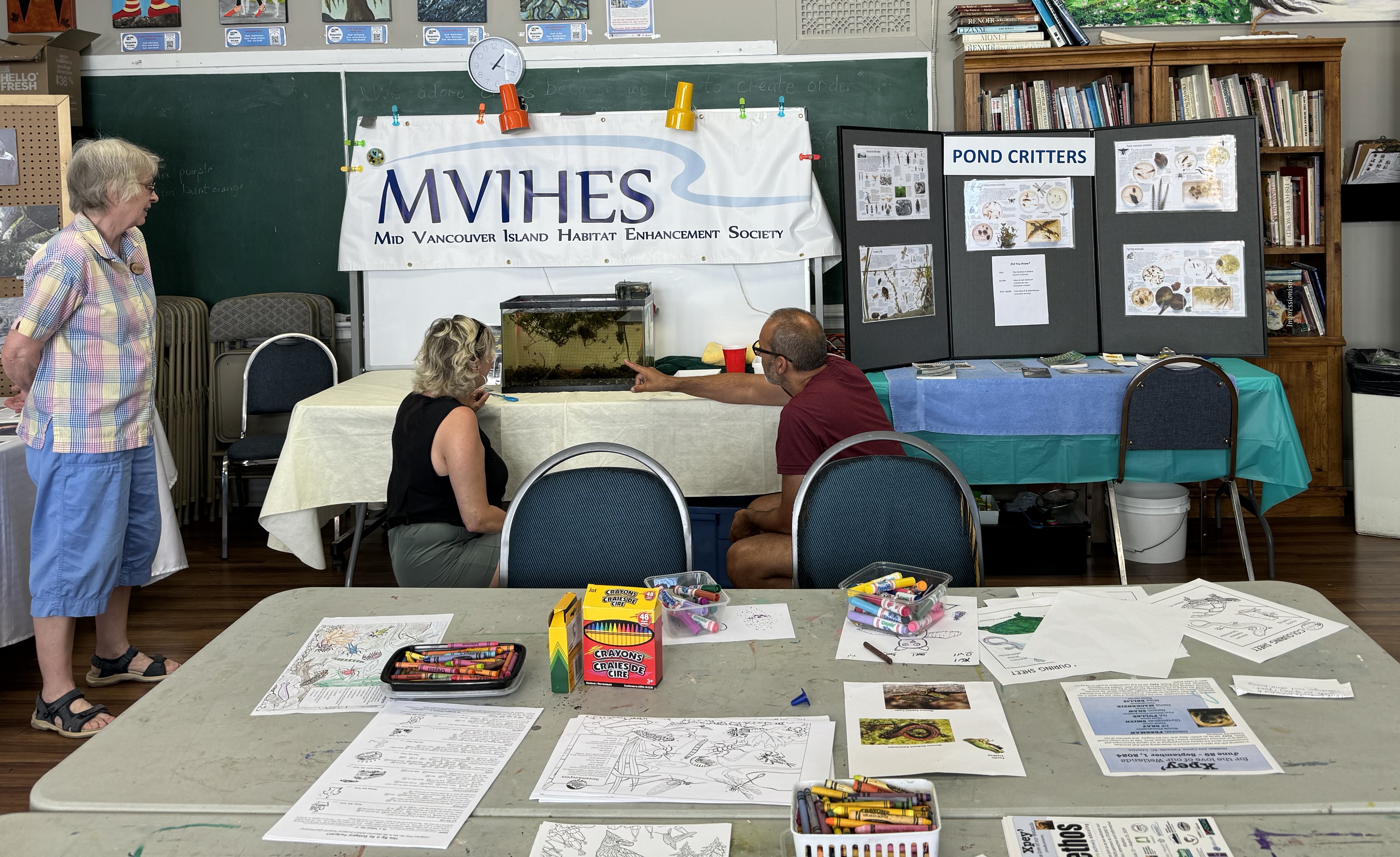

Other folks who came out to plant on October 18 were (left to right): Nancy Pezel (MVIHES), Dave Hutchings (Arrowsmith Naturalists), Parks staff Logan, Enrique, Sean, Ethan, and Aimee, Mike Shillingford (Volunteer at Large). Photo taken by Barb Riordan (MVIHES).

And let's not forget Graham Gidden, Manager of Parks.

Many thanks to the Ballenas ROAM students and teacher, Parksville Parks Department, and our volunteers. The coffee and donuts were great, too!